April 2023

A great quote

Chasing artificial performance

The promise of Artificial Intelligence is real. Culling thousands of annual reports in less time than humans take to read just one gives hope to the traditional active stock picking industry - an industry that claims skill in scanning the 10,000+ publicly traded companies for identifying those that will outperform broader market indexes.

It is little surprise, then, that ChatGPT has renewed hope in AI-based investment products such as the AI Powered Equity ETF (AIEQ) featured by Business Insider at the end of January: Forget ChatGPT — an AI-Powered ETF Is Beating the Market by Nearly 100%.

Beating the market by nearly 100%? Sign me up!

Well, Thinking in Likelyhoods tells a different story...

The window for this article’s observed performance was one month. Anything can happen for just one month. So in true Likelyhoods form, I started tracking AIEQ’s performance beyond the short life span of most eye-popping headlines like this one.

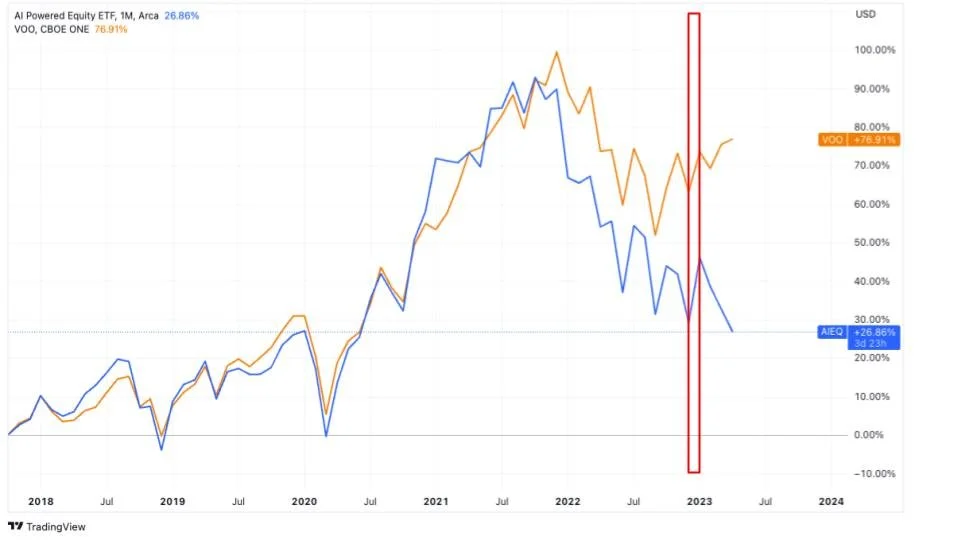

If you have not already suspected where all this was going… yep, it’s that narrow red rectangle from January 1st through January 31st:

Source: TradingView

A few observations:

Since inception on October 17, 2017 through April 21, 2023, AIEQ returned just 26.86% versus 76.91% from the Vanguard 500 Index Fund ETF (VOO) return.

In case you are wondering about expense ratios, AIEQ charges 0.75% while VOO charges 0.03%. Seriously.

Unless investors are trading on one month horizons, this article should not convince anyone to invest in AIEQ…

…but it has! check out the surge in inflows immediately following January’s publicity:

Source: ETF Database

Thinking in Likelyhoods means not being drawn to the newest shiny object, biting on head fakes, or chasing performance. And there’s a lot of performance-chasing in this industry. Investing through a reliable decision-making process is more important than ever, not based on one article, one trendy thesis, or (gasp) a one month headfake.

Now, I may be wrong of course. From inception through September 2021 AIEQ essentially matched VOO’s returns. 2022 was a tough year for AIEQ, but maybe AIEQ took advantage of the selloff to snatch up equities poised to outperform in 2023? Or maybe the ChatGPT technology is sufficiently better than IBM’s Watson technology (and the fintech firm Equbot) to justify resetting the comparison in this post-ChatGPT world in which we now live?

I will say, I am skeptical until convincing evidence proves otherwise. There’s one way to find out. I will start tracking this comparison periodically - as I do around here - and will report back to you with the findings.

Indicators: Leading or Lagging?

Markets are forward-looking, so Leading Indicators seem a natural place for investors to look for signals on the future direction of markets.

Indeed, pieces like MarketWatch’s U.S. economy is headed for trouble, leading economic index signals lean on Leading Indicators to forecast trouble for the US economy.

In fact, some investors question the utility of lagging indicators entirely. Such indicators reflect water under the bridge, and efficient markets have already priced in those data points, so there is no predictive value in investing on the basis of lagging indicators.

The reasoning behind both claims, in favor of leading indicators and against lagging indicators, is highly flawed.

The economy is dynamic and complex. It is virtually (entirely?) impossible to isolate the influence of one economic variable while controlling for the influences of all other economic variables, the statistical process that is required to move beyond correlational relationships into causality. History offers plenty of examples illustrating the dangers of backtesting for correlational or even coincidental relationships that inevitably revert back to long term baselines. With literally thousands of economic variables to build into backtests, one is certain to find some combination of variables that fits the noise in historical data.

In The Signal and the Noise, Nate Silver offers priceless insights based in data:

“Even the well-regarded Leading Economic Index, a composite of ten economic indicators published by the Conference Board, has had its share of problems. The Leading Economic Index has generally declined a couple of months in advance of recessions. But it has given roughly as many false alarms - including most infamously in 1984, when it sharply declined for three straight months, signaling a recession, but the economy continued to zoom upward at a 6 percent rate of growth. Some studies have even claimed that the Leading Economic Index has no predictive power at all when applied in real time.

"There's very little that's really predictive," Hatzius told me. "Figuring out what's truly causal and what's correlation is very difficult to do."

…

Hatzius noted, for instance, that the unemployment rate is usually taken to be a lagging indicator. And sometimes it is. After a recession, businesses may not hire new employees until they are confident about the prospects for recovery, and it can take a long time to get all the unemployed back to work again. But the unemployment rate can also be a leading indicator for consumer demand, since unemployed people don't have much ability to purchase new goods and services. During recessions, the economy can fall into a vicious cycle: businesses won't hire until they see more consumer demand, but consumer demand is low because businesses aren't hiring and consumers can't afford their products.

Consumer confidence is another notoriously tricky variable. Sometimes consumers are among the first to pick up warning signs in the economy. But they can also be among the last to detect recoveries, with the public often perceiving the economy to be in recession long after a recession is technically over. Thus, economists debate whether consumer confidence is a leading or lagging indicator, and the answer may be contingent on the point in the business cycle the economy finds itself at. Moreover, since consumer confidence affects consumer behavior, there may be all kinds of feedback loops between expectations about the economy and the reality of it.” (pp187-188)

ONE MORE THING…

A great quote. As Cliff Asness, a founder at AQR Capital Management, told an investing conference at Columbia Business School last week: "The definition of insanity is doing the same thing over and over and expecting a different outcome. Sticking with a great investment process when it feels like it’s punishing you over and over isn’t 'the definition of insanity.' It’s your job.” What a Difference a Year Makes (WSJ)

The information and opinions contained in this newsletter are for background and informational/educational purposes only. The information herein is not personalized investment advice nor an investment recommendation on the part of Likely Capital Management, LLC (“Likely Capital”). No portion of the commentary included herein is to be construed as an offer or a solicitation to effect any transaction in securities. No representation, warranty, or undertaking, express or implied, is given as to the accuracy or completeness of the information or opinions contained herein, and no liability is accepted as to the accuracy or completeness of any such information or opinions.

Past performance is not indicative of future performance. There can be no assurance that any investment described herein will replicate its past performance or achieve its current objectives.

Copyright in this newsletter is owned by Likely Capital unless otherwise indicated. The unauthorized use of any material herein may violate numerous statutes, regulations and laws, including, but not limited to, copyright or trademark laws.

Any third-party web sites (“Linked Sites”) or services linked to by this newsletter are not under our control, and therefore we take no responsibility for the Linked Site’s content. The inclusion of any Linked Site does not imply endorsement by Likely Capital of the Linked Site. Use of any such Linked Site is at the user’s own risk.